A small 'Halt' (below the dignity of even most ordinary passenger trains) station in west UP, Kafurpur was the place where we often went as children for our summer holidays (and sometimes winter ones as well). That's where my eldest Tauji (father's elder brother) was posted as the stationmaster.

The reason for the larger paternal joint family gathering there would probably be the presence of either or both of my paternal grandparents (Ammaji and Babaji).

Being the stationmaster gave my Tauji a lot of importance and dignity in the surroundings, including, of course, the station premises. We children sort of lived in that reflected glory, happy to strut around officiously and without care.

There was no electricity, water was from the handpump, and there were mango trees all over, which gave off real mangoes. Mustard and sugarcane fields nearby completed this incredibly pastoral scene. But one shat in latrines of the manual kind, where the stuff accumulated below in metal containers, which must have been removed by hand by a thus-assigned caste person periodically. The younger children (including me) however did the act directly outside, in spritual communion with mother nature.

Most of us kids had come from restrictive urban environments and thus must have found the rural spread and simplicity (seeming like that to us, then) of Kafurpur brilliant. For me (and my younger brother Aloke) the highlight were the stacks of used cardboard railway tickets we induced Tauji to hand over to us, after he was through with collecting them from alighting passengers. I remember he looked grand in his black railway official coat, kindly but firmly standing at the informal exit of the station, and collecting those treasures.

Not too many passenger trains actually stopped at Kafurpur halt. I think in the whole day there were possibly only two. The rest whizzed past, including some express trains, on their way possibly to Delhi or Moradabad. Possibly Kafurpur was in the Delhi-Moradabad route, with stations like Amroha, Gajraula and Garhmukteshwar nearby. We usually travelled from Calcutta in an Express train upto Moradabad, and then changed there into a passenger train for Kafurpur.

There was intersting exchange of a metal ball placed in a larger metal ring, each time an engine rushed past. One came from the running train, another was given to it. Then that ball was inserted in some formal and mysterious looking large mechanical contraption fixed inside the stationmaster's cabin. This activity resulted in a authoritative-sounding metallic gurgle which seemed to me terribly important and insider-stuff, and I felt privileged.

The winters were bitter and fun. Coal-fires (or was it wood?) kept the temperature friendly (literally as well as figuratively). The comfortably warm and cosy stationmaster's cabin at night was a dream, with a pitch dark freezing neighbourhood outside, and the dramatic aural hurly-burly of the occasional through express. On one such night in that unreal den part of my posterior (actually the side view) got too close to the amiable fire. It was some time before I realised that my skin was badly scalded.

On another occasion we children decided to derail a train. Carefully and scientifically we placed the smooth round stones (ballast, I believe they are called) one by one in a straight line on top of the streakily polished rail track, probably to a distance of about 5 feet or under. Then we waited, half-fearful and half-excited of our deed. The scene-to-be played in our heads (at least it did in mine), with dreadful visuals of the consequences. Finally a train appeared, and passed safely over. To this day I wonder about our good luck.

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Saturday, March 25, 2006

More About Ila

I met Ila in 1979. I was 19 then. She must have been few months younger.

Ila was a slightly chubby, reasonably pretty, happy, upper middle class teenager, like any other. Not particularly intelligent, nor significantly dumb. I fell in love - in retrospect, with the idea of Ila in my mush inclined head.

Poor girl. For the next three years, and much beyond, I must have stood for her as an unhappy example of a gentleman pest, fruitlessly bombarding her unwilling but consistently polite self with half-digested ideas of revolution and the meaning of life. My virginal attentions, devoid of any thoughts of real physical contact, must have seemed to her quite odd.

But Ila was a very decent human being. All through the time I knew her (she later got married and went off to Ohio) she never ever (not even once) ticked me off for being so annoyingly persistent. For a very long time afterwards she personified chaste virtuous love for me. I even ran a company called Ila Film & Video (after graduating from FTII) for a few years.

The female lead in my FTII diploma film "Avkash Kal" is called Ila.

Ila was a slightly chubby, reasonably pretty, happy, upper middle class teenager, like any other. Not particularly intelligent, nor significantly dumb. I fell in love - in retrospect, with the idea of Ila in my mush inclined head.

Poor girl. For the next three years, and much beyond, I must have stood for her as an unhappy example of a gentleman pest, fruitlessly bombarding her unwilling but consistently polite self with half-digested ideas of revolution and the meaning of life. My virginal attentions, devoid of any thoughts of real physical contact, must have seemed to her quite odd.

But Ila was a very decent human being. All through the time I knew her (she later got married and went off to Ohio) she never ever (not even once) ticked me off for being so annoyingly persistent. For a very long time afterwards she personified chaste virtuous love for me. I even ran a company called Ila Film & Video (after graduating from FTII) for a few years.

The female lead in my FTII diploma film "Avkash Kal" is called Ila.

Thursday, March 23, 2006

Ek Thi Ila

Monday, March 20, 2006

Pen, Paisa, Monthly, Chasma

I grew up in a back of the beyond suburb of Calcutta (now Kolkata) in the 70s. It was called Belghoria (it still is called by the same name, and I still don’t know why and, quite surprisingly, I have never ever been curious to know why).

In 1970 I was 10. I left in 1979, for Delhi.

I have mixed feelings towards Belghoria. It is where I spent much of my growing years. It is also where I felt economically, intellectually deprived - a frog in a hopeless, humourless, prosaic well.

Don’t get me wrong. My parents (bless them!) tried their utmost to provide us four siblings the best they could. But my father was an incurable dreamer, scheming his next big capitalist move every now & then, of course without much success. Trust him to have left a comfy permanent service (of a decade or so long) in a Central government outfit, and move with four young children and an unwilling wife from a familiar & much loved Delhi to an unknown outpost called Calcutta, on the basis of a later-proved-dubious offer from a well-off childhood ‘friend’. He spent most of his working years in Calcutta fighting the sure slide of the family into a barely lower-middle-class existence.

One of his failed ventures (‘Associated Data Processing’, I think, when computers were just coming in – before that he had tried PVC sheets & pipes, if I remember right) left him with a Remington portable typewriter as the lone surviving asset. I still have it. In fact in my pre-PC avatar (not so long back), I used it extensively, lugging the heavy ‘portable’ wherever I went in search of greener pastures – Delhi, Mumbai, Jaipur, Pune, Ahmedabad… My first (and only, till date) feature film script was painstakingly typed using this beautiful, messy mechanical gadget. Mind you, an error on a page meant retyping the whole damn thing all over again (using the liquid whitener meant smudgy letterforms, and I am an incurable perfectionist).

I love my father. The older I become, the more I find myself in his image. He is the one who blindly supported me, much beyond his means, in my often foolish ventures. I was able to go to FTII only because of him – my elder sisters, younger brother and mother knew very well that the family’s economic circumstances could hardly sustain the exorbitant expenses (to us then) of me staying in Pune. And cinema was an inadvisable profession for a middle class lad to try and get into.

I am glad I went to Pune, however. FTII and the dreamy 3-year stint there gave me a clear direction and purpose in life.

Thank you Chachaji (that’s what we call our father, probably because we were originally growing up in a loose joint family, where my father was the youngest brother, and hence Chachaji to most children). Thank you Mummy. Thank you Sandhya, Deepa and Aloke. I am truly grateful.

Coming back to the title of this piece. My father was a slightly forgetful person. So everyday, when he had to leave for work in the morning, either my mother or one of us would remind him of having taken – Pen, Paisa, Monthly, Chasma. The monthly (railway pass) meant it was the phase when he was catching the local train daily to go to Calcutta city proper (earlier he used to work in Belghoria itself, walking back home in the afternoon break, for lunch and perhaps a quick snooze - I sometimes get to do it nowadays - the wheel of life inevitably & uncannily churns).

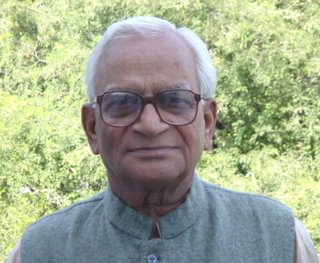

Chachaji is past 75 now.

Friday, March 17, 2006

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)